Can we imagine a modern world without microchips? Today, it’s almost impossible. From smartphones to combat drones, from healthcare systems to solar panels, tiny semiconductors lie at the heart of global infrastructure.

That’s why they have become the new arena of political and economic struggle. Donald Trump, bidding to return to the White House, is banking on aggressive tariffs to bring chip manufacturing back to the US. But can America, even with its industrial might, dislodge Asia from its pedestal?

Why Are Semiconductors the New Oil?

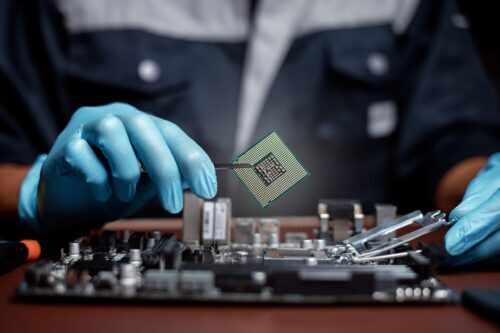

Semiconductors are not just “parts” for gadgets. They are the foundation of all modern electronics. They process signals, control currents, make devices work, and everything from security to economic growth depends on them.

From a geopolitical perspective, controlling their production gives you leverage. That’s why the U.S. doesn’t want to depend on supplies from China, and especially not from Taiwan, a politically unstable region that nevertheless produces more than 50% of the world’s microchips.

The center of this industry is TSMC, a company whose manufacturing facilities serve giants like Apple and Nvidia. Its technological backlog is so large that even China, despite its ambitions, is one step behind.

A Battle of Competencies

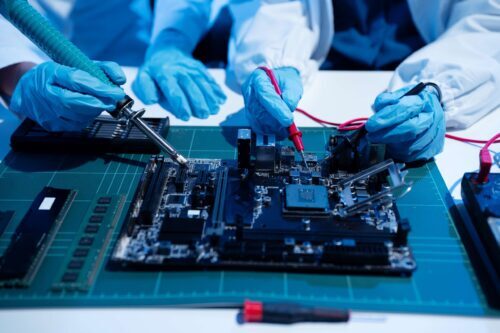

Even if investment in U.S. factories continues, as it did under Biden’s CHIPS and Science Act, one key problem remains: people.

TSMC, which built a factory in Arizona, faced the trivial but critical problem of a shortage of specialists. As a result, thousands of engineers were moved from Taiwan to set up the process. This shows the lack of a systematic approach in the U.S. to training the engineering workforce needed for such a complex industry.

Now, point by point, what problems the U.S. faces as it tries to ramp up semiconductor production at home:

- Shortage of skilled engineers. High-precision manufacturing requires highly specialized skills that are simply not available in the US.

- Immigration restrictions. Protectionist visa policies limit the influx of those specialists from India, China, and Taiwan.

- Difficulties in building factories. Erecting chip factories takes years and requires ideal conditions, including a stable power supply and high-purity water.

- Rising costs. It costs more to build and operate factories in the U.S. than in Asia, even with subsidies.

- Fragmented strategies. Lack of long-term coordination between government, business, and universities slows overall progress.

Plus, tariffs could hit American companies: Apple, Nvidia, Intel, and others whose businesses depend on uninterrupted supplies.

What’s Next?

The reality is that the U.S. can’t become a leader in semiconductor manufacturing overnight by imposing tariffs alone. It needs long-term planning, alignment between federal and private initiatives, education, and immigration reform.

Perhaps a different question should be asked: Does the United States need complete control of the supply chain? Or is it wiser to diversify risk by investing in reliable partners from Japan to India?

While the U.S. builds defensive walls, China, Taiwan, and South Korea continue to strengthen their position through science, R&D, and government support.

The semiconductor race will not be a quick one. But the outcome will be determined less by taxes than by the ability of countries to think strategically.